HISTORY

The Beginnings of Time

Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) began life as a simple way for mariners to calculate their longitude, in an age when every region just set its own clocks according to whatever time local people chose. By the mid-19th century GMT was being used to standardise time across the fast-growing British railway system, and in 1880 it was legally adopted throughout Great Britain. Greenwich Mean Time had become the only time in town.

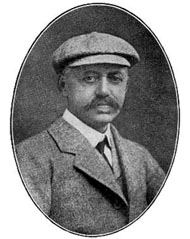

Then, around a hundred years ago, a prominent English builder called William Willett noticed how many of his fellow Londoners slept right through a large part of the summer day. A keen golfer, Willett saw the opportunity to get an extra round in before sunset if the clocks could be put forward for an hour during the summer.

“While daylight surrounds us, cheerfulness reigns, anxieties press less heavily and courage is bred for the struggle of life.” – William Willett, 1907

“While daylight surrounds us, cheerfulness reigns, anxieties press less heavily and courage is bred for the struggle of life.” – William Willett, 1907

Willett (who was, incidentally, the great-great-grandfather of Coldplay’s Chris Martin) spent the rest of his life campaigning for the clocks to change so that more people could make best use of the available daylight. Just one year after his death in 1915, Willett’s dream finally came true when Parliament passed the Summer Time Act. The young Winston Churchill spoke in favour of the change, pointing out that, “William Willett does not propose a change from natural time to artificial time, but rather that we substitute a convenient standard of artificial time for an inconvenient one.”

The Act advanced the clocks in Great Britain for one hour from 21st May until 1st October, in order to save coal for the war effort and help ease some of the hardships caused by air-raid blackouts. People in Britain liked the new Summer Time so much that we decided to keep it, establishing the model that we're all familiar with today: GMT in the winter and GMT+1 in the summer.

World War II

For seven years during World War II Britain set its clocks one extra hour forward throughout the year, in order to gain even more of the same benefits that the original Summer Time change had brought: increased workforce productivity, boosted morale, saved energy and reduced danger from air raids. It worked because GMT+1 in winter and GMT+2 in summer meant most people spent more of their waking hours in the daylight. When the war ended, however, the clocks went back to their peacetime settings.

The British Standard Time Experiment

From 1968 to 1971 the British Government ran an experiment to see what would happen if we dropped the clock change altogether and just stuck with GMT+1 all year round.

The main result was a reduction of 3% in the number of deaths on the road – and an 8.6% reduction in Scotland. But this information was never communicated to the public, partly because of initial difficulties with unpicking the effect of the recent introduction of new drink driving laws on the statistics. All the public heard at the time was that there was a slight increase in the number of road deaths in Scotland during the darker mornings. These tragic deaths were widely reported in the press, the experiment was blamed for the increase and many people turned against the idea.

In truth, the reduction in the number of road deaths in the lighter evenings was more than twice as great as the morning increase, meaning that around 40 fewer people were killed or seriously injured on Scotland’s roads during each year of the experiment. But good news doesn't sell, and this significant overall reduction in road casualties went unreported.

Although a small majority of British people polled in favour of keeping the clock change in 1970, the experiment had failed politically. An overwhelming majority of MPs voted against keeping the change, and the idea sank like a stone for another 25 years.

Recent adventures

Over the past three decades a series of EC Directives have led to the clocks all across Europe being changed on the same date as clocks in the UK – the last Sunday of March and the last Sunday of October. But here in Britain, an incredible eight attempts in Parliament since 1994 to change our own clock times have each come to nothing. Bill after bill has been ‘talked out’ of Parliament – in other words, debated until the time ran out.

The 2006 Energy Saving (Daylight) Bill, which called for a new three-year experiment to advance the clocks by one hour throughout the year, was talked out before a decision could be made, despite a vote in the House of Commons which came down in favour of the change. Unfortunately fewer than 100 MPs voted – not enough for the vote to count.

The 2010 Daylight Saving Bill

Number’s were not a problem at the last vote on Rebecca Harris MP’s Daylight Saving Bill. After a landslide at its first vote in December 2010, the bill was up in the house again on January 20 2011, with the backing of both the 90 plus organisations that make up the Lighter Later coalition and the UK Government itself who had stated that it wanted the bill to pass.

The Daylight Saving Bill took a slightly different approach to its predecessors, calling for a review of the evidence for and against a change to our clocks, only after which a trial of a new time setting would be conducted. A move to a trial would be reliant on concensus across the devolved administrations of the UK.

The bill garnered more support for the issue than ever before. Over 150 MPs attended the last debate in parliament to vote in favour, with just 10 voting against. Even with overwhelming backing the bill was talked out by just three MPs. The anger and frustration amongst supportive MPs and the government was palpable.

Ed Davey MP, the then minister responsible, said: “The Government is clear that this is an issue which many MPs will want to return to, and in the next session of Parliament - only a few months away - it is possible that another backbencher will wish to pick up Rebecca Harris’ Bill. Given it was amended in committee to secure Government support, any MP choosing to do so is likely to have more reassurance that the Bill would then have a smooth and more rapid passage.”

Here comes the sun

Over the years the evidence for the positive effects of shifting the clocks forward by an hour has mounted, with the latest academic research showing that the change could save over 80 lives and at least half a million tonnes of CO2 emissions every year. Knock-on benefits of reduced electricity bills, improved health and a boost for the leisure and tourism sector mean that lighter evenings now have a wider range of supporters than ever. From tourism trade bodies to road safety campaigners, and from sporting organisations to serving government ministers, a new and diverse movement for lighter evenings is growing day by day.

Meanwhile opposition to the change is melting. Today, the old arguments about milkmen and postal workers needing early-morning sunlight to carry out deliveries look exactly like what they are – arguments from the 1970s. The National Farmers Union, which had been a vocal critic of earlier proposals, recently announced that the reasons for farmers’ past opposition to advancing the clocks had been “lost in history”, and that they no longer mind one way or the other.

This is an idea whose time has come. We could soon be enjoying an extra hour of evening sunshine every day.